The Magicians

Behind Oklahoma’s Mushrooms

Are you a mycophile, or a mycophobe?

The answer depends on how you perceive mushrooms. Do you consider them a culinary delicacy? The base for a healing tincture? Do you abandon civilization each spring to go forage morels? If you associate mushrooms positively with their culinary, medicinal or even recreational purposes you might be a mycophile.

If, on the other hand, you regard mushrooms warily, picking them out of salads and stepping around them on hikes, you are probably a mycophobe. You might think mushrooms are notoriously deceptive and deadly, not to mention strange—silently, even eerily, cropping out of objects living and dead in the damp dark of night. Friend or foe? One thing most people can agree on is that mushrooms are mysterious little organisms.

Even after walking through the growing process with no fewer than three mushroom farmers, I find the mushroom life cycle to be no less mysterious. Unlike raising traditional crops, which require a basic combination of seed, soil, sun and water, commercial mushroom farming is a lab-based process involving complicated terminology such as agar, spawn, mycelium and pasteurization. Certainly all farming is rooted in science but mushroom farming looks a lot like mad science; if it were a cartoon it would look less like “Old MacDonald” and more like “Pinky and the Brain.”

I ask JD Merryweather of Oklahoma Mushroom to bring mushroom farming down to kindergarten level for me.

“Mushrooms are like humans in that they breathe oxygen and expel CO2,” he begins, and I nod, fully grasping this analogy. From there, his explanation veers sharply into a scientific description of inoculating spawn in a sterile environment, and mushrooms taking over the substrates to build root systems.

My eyes glaze over and I decide I’m probably not a full mycophile.

The tidy science of mushroom making is what drew Katie Kelton and Angela Marsh to start Victus Mushroom Farm in Broken Arrow. The women, whose husbands own Karma Tattoo & Body Piercing, became familiar with the process of sterilization through their time at the studio. Looking for an outlet of their own, Kelton and Marsh experimented with a mushroom kit in the tattoo studio before heading to the Telluride Mushroom Festival, where they found a community of like-minded mycophiles. Upon their return, the duo moved out of the tattoo parlor and into their own space.

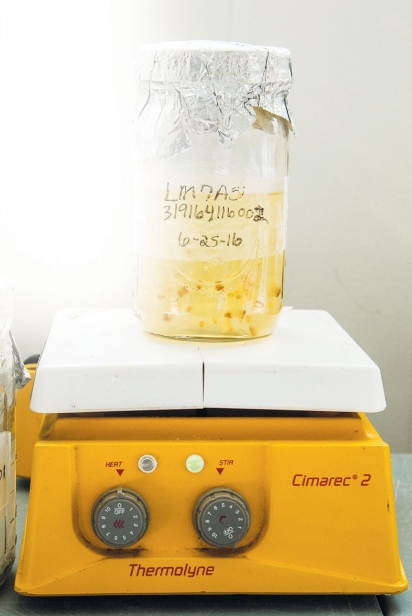

Their mushroom “farm” is an industrial series of rooms through which the mushrooms progress, starting in the annex. Here, a wall-sized whiteboard is covered in recipes, notes and detailed illustrations of the company mascot, Mr. Victus, and his squad drawn by Marsh’s kids who often join her at the farm. Nearby, wheat berries are softened through boiling and then pressure-cooked to sterilize.

Adjacent to the annex, a small sterile room they call the lab is where the mushroom making begins. A small refrigerator holds petri dishes full of agar, a gelatin made from seaweed. Spores are placed on the agar until the baby mushrooms begin to spread their wings (or central nervous system, as the case may be). At this stage, the mushroom looks not like a mushroom at all, more like a thick white cobweb called mycelium. The mycelium is placed on sterilized wood or wheat grain, which it begins to consume like compost. From here the mycelium is packed tightly into bags, sterilized, mixed with more food and additives, then placed in a cool, dark room. Inside the bags the mycelium mixture heats up and sprouts from within these casings until the mushrooms are ready for harvest.

In Oklahoma, mushroom farming has not yet taken off the same way, say, craft beer has. Victus, in operation for only a year, can be found at the Cherry Street Farmers’ Market, where they routinely sell out well before closing time. Soon, there will be a new kid on the block. Merryweather, a founding member of COOP Ale Works out of Oklahoma City, has taken over an existing operation, Oklahoma Mushroom, and plans to bring his mushrooms to the Cherry Street market as well.

I ask him if there are any parallels between craft brewing and craft mushrooming. To my mind, they are both delicate, lab-based sciences. Merryweather is not the master brewer behind COOP, however. He is the creative force behind their marketing and sales team, the man responsible for plying restaurants and stores across the land with COOP, and convincing major-brand-drinking Oklahomans that it is possible to enjoy a locally crafted dark beer.

This is the kind of work he plans to bring to Oklahoma Mushroom: branding, partnerships and education. We can expect to find shiitake and lion’s mane varieties, in addition to rotating specialties such as oysters, beech whites and maitakes, featured in select restaurants throughout the state, including Tulsa’s Hey Mambo. In Oklahoma City, the Asian District will serve as a customer base for both fresh and dried mushrooms, keeping Merryweather operational year-round.

While Merryweather and the women at Victus focus on niche markets, Pat Jurgensmeyer at J-M Farms, based in Miami, Oklahoma, sees the bigger picture.

“If you look at other [mushroom] farms across the country, we’re on the bottom end of the large side, if the scale is small, medium and large,” Jurgensmeyer says.

In operation since 1979, J-M farms employs about 500 more people than Victus or Oklahoma Mushroom. The farm was started by Jurgensmeyer’s father and it remains a family-run business, marketing their mushrooms regionally as locally grown.

On a national level, Jurgensmeyer chairs the Mushroom Council’s region 1 (which includes the whole of the United States except California and Pennsylvania), where he works on nutritional research and promotion. One of the Council’s primary initiatives is the Blended Burger, a burger patty in which at least 25% of the meat is replaced with fresh, chopped mushrooms. Not only is the Blended Burger more nutritious, it’s more economical. Using the Blend allows meat to go further in budget-tight facilities, like schools.

At the behest of the Mushroom Council, Blended Burger battles have spread across the country. More than just a marketing ploy, the Blended Burger Project seeks to improve the nutritional value and reduce the carbon footprint of one of America’s favorite meals. Tulsa’s Kitchen 66 hosted a Blended Burger Battle in June of this year, which fed into the James Beard Foundation’s second annual Blended Burger Project competition.

Though JD Merryweather doesn’t dismiss the value of the Blended project (he plans to look into shiitake-based recipes), the Blend won’t likely be a large part of Oklahoma Mushroom’s marketing plan. He’d prefer to craft mushrooms that stand on their own in salads and pastas, mushrooms that local chefs vie for and market-goers fawn over.

In short, he hopes to make mycophiles of us all.